Ongoing

Dialogue #05

Diogo Evangelista + José Taborda

A line has two sides

Until 19 October - Dialogue Project Space

I'm not a writer or a critic, nor do I know what kind of framework and meaning these "room sheet" texts should have in a visual arts exhibition. I'm just a spectator - emancipated or not, I sound better than an observer. In fact, I've tried to choose a hypothetical reader to write to and I've chosen the two of you who prepared this exhibition.

To summarise, I'm trying to speak to you from three conditions: that of the spectator, that of illusion as a possibility and the condition of the space of this exhibition.

As a spectator, I take on the force of the meaning of the term spectare, as expectation, that is, an operation of the nature of waiting and desire, in this case, an expectation to experience a metabolisation in myself from what I am given to see. Expectant about what can produce imponderable effects on the mental faculties, translating into a broadening of my perplexity about the world. This could be the raison d'être of an expository experience. Which, in this case, is presented in a chapel, "setting" of what is called the sacred theatre or liturgy.

The Hellenes, sitting in a theatre, were waiting for catharsis. In Hamlet, it is the illusion that brings out the deepest truth in the beholder: "I have heard that there are criminals who, when watching a theatre performance, are so impressed by the fascination of the illusion that they immediately reveal their guilt; for although murder has no tongue, it is forced to speak by even more prodigious organs." This quote comes from the moment when Hamlet, in the play, projects another piece of theatre in order to ascertain the secret truth of the spectators.

This seems to be a vital necessity. Not to shorten the criteria for the acceleration of the senses, but rather to expect from art the stimulation that seems to gauge a truth through "even more prodigious organs" than those that can be brought to the scalpel. Organs that are the stuff of psychic states, states of soul, the Humours. All this to say that, as in these examples, this exhibition, it seems that the dominant cognitive function of the spectator is actually that of the intuition-expectant capable of the "fascination of illusion". Therefore, what we see is something else that is always something else. Simultaneously and paradoxically, it is the opposite of camouflage, it is illusion realised, of constant bewilderment because what you see is [not] what you see. It's always another condition of illusion as the possibility of a deeper, denser truth. So we add the condition of expecting to the certainty of seeing illusion activated as a possibility.

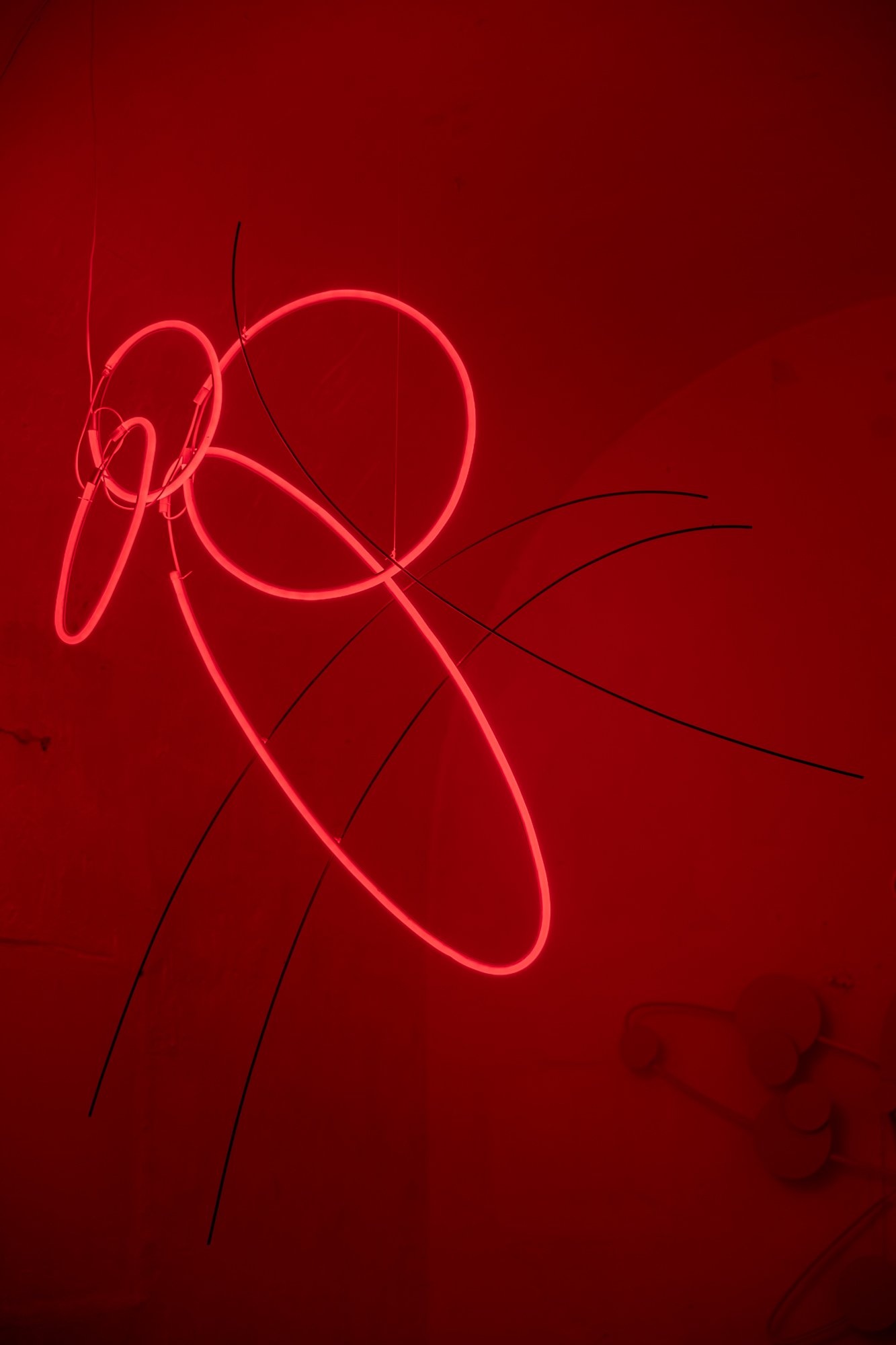

In your works there is a movement made up of fluctuation and simultaneity, in the ambiguity of a line whose sides demarcate a hinge of itself. In modelling Light-Space, the images are spectral, kaleidoscopic, as close to the origin as they are elusive.

In this sense, to deal with the third and final condition, space or circumstance, I remembered Walter Benjamin's definition of the origin of works of art. When he says that they arose "in the service of a ritual, first magical and then religious. It is therefore of decisive importance that the form of existence of this aura, in the work of art, is never completely detached from its ritual function. In other words, the singular value of the 'authentic' work of art has its foundation in the ritual in which it acquired its original and first use value."

Rituals today live in a time of heterodox, omnipresent and simultaneously marginal manifestations, but they continue to unveil the leaden mist of banality. They emerge from collective or individual systems as experiences where reality symbolically becomes something else.

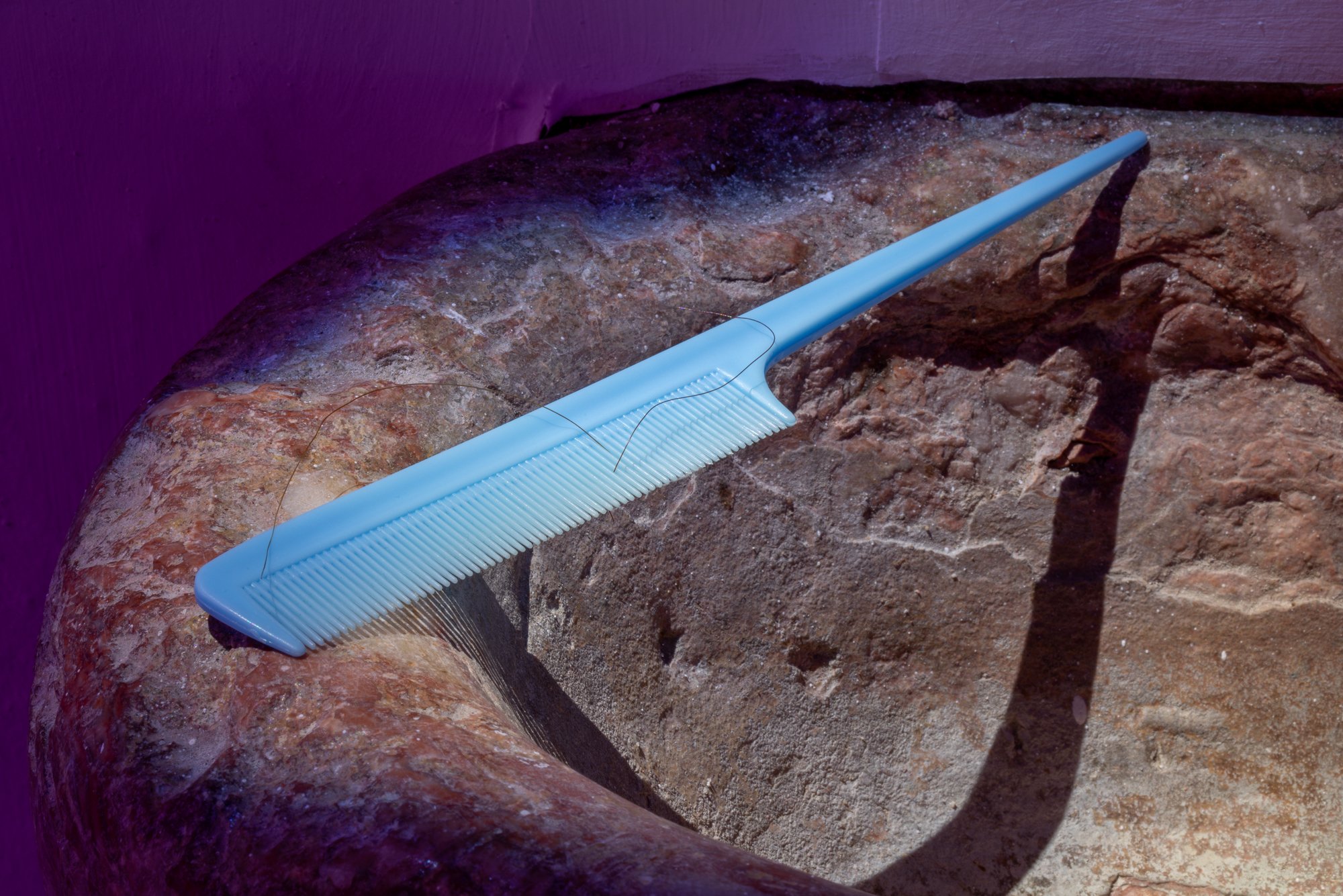

Here, your works take us into that realm: the light that fixes orbital drawings, a dreamlike lamp, a mammoth hair resting on an ordinary comb. They open up to the strangeness of the ritualistic function of objects. Just like the ethnographic objects that once had a powerful attraction for modern artists. Documents that were destined for a magical, religious use that was totally unknown to them, which is why they were heavy instigators of dissent. They deconstructed a certain worn-out way of symbolising the mysterious disturbing forces of a positivist West.

In your exhibition, there is a conceptual densification of the pieces that comes from the nature of the space. They don't evoke a ritual morphology, but the space is silently responsible for taking us into the sphere of a certain religious emotion. The space, even if stripped of symbols, makes us simultaneous to the idea of blindness. A blindness that is deliberate, by those who seek another kind of unintelligible light. By those who make themselves blind in order to activate another kind of vision. As if it were an unwritten commandment - or a beatitude - that said: "Happy are those who make themselves blind because they will perceive things from within". Something like this happens in that cut to the eye that Buñuel offers us in Un Chien Andalou (1929), or even in Duchamp's critique of retinal art. Making oneself blind as an imperative for the spectator.

In this space, what disappeared was not the sacred, but its representation. Because the sacred is not thingified as something that is or ceases to be. This chapel emptied of its original iconographic programme gives way to absence, to the void that can be the culmination of all representations of God. In this absence, a clearing opens up for the birth of other ways of life, inaugurating a difficult requirement, that of not creating a levelling of the spirit of the place (genius loci).

Ever since Weber, I've thought that the disenchantment of the world isn't, or can't be, about denuding it of the sacred, but rather about taking on the transpositions of the phenomenon of religion into other forms of existence, such as contemporary art. It's important here not to remain disenchanted, but to densify it by means of visual and intellectual artifices that are capable of stirring up a certain somnambulism. The re-enchanted world is not a return to an alienated dismissal of life, which seeks some kind of unaccountable alibi, blaming it on the world of belief. It's the opposite. It's the spectators who make the works - that's why my hypothesis, raised here, is that it's impossible to desacralise spaces, because it's not up to anyone to delimit what is or isn't sacred, what is or isn't inhabited by magic and the fascination of illusion.

João Sarmento SJ